The fastest typist I’ve ever seen was a guy I used to work with. When he started going it sounded like a machine gun. Our standard line when people asked the rest of us about him was, “Yeah, he types over 150 words per minute … and about 40 of them are spelled right.”

Even after you ran his stuff through a spell checker, you’d have to proof-read very carefully to catch the places where “there” and “their” were mixed up. Where single letters showed up at random because the spell checker skips one-letter “words”. Where he left out words or just plain didn’t make any sense.

It usually took longer to fix his stuff that it would have taken to do it yourself from scratch. So why did we put up with it? Well, he was the boss. Keen.

But like anything else in life, you can at least learn something from the situation. What I learned from him was that it doesn’t matter how much you produce if no one wants it. Or put another way: Anything you do for someone else that isn’t up to their standards doesn’t count.

For an example of an entire industry that’s working as hard as possible to ignore this simple truth, compare television today to what it looked like in the 1950s.

The golden age

Back then there were three networks. How many prime-time shows did they collectively produce per week? Counting 8-11 p.m. Monday through Friday, that’s three 1-hour slots x five days x three networks = 45 hours of programming. Lets say a third of those hours were broken up into half-hour shows, so a total of 60 shows per week.

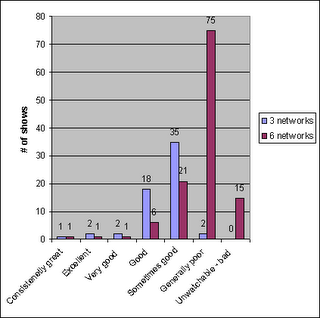

Let’s assume that to have a consistently great show you needed six extremely talented writers and actors. (Yes, there’s a lot more to it. This is just an example.) The fewer good people you have, the less often your show will be good. To fill 60 shows, you might have the following mix:

| Show quality | Talented staff per show |

# of shows | Total talented staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently great | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Excellent | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Very good | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Good | 3 | 18 | 54 |

| Sometimes good | 2 | 35 | 70 |

| Generally poor | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 60 | 150 | |

Obviously every network would like their shows to be better. But for whatever reasons there are only 150 people with the level of talent needed to produce a weekly show.

Double the output

Fast forward a couple of decades. Now there are six networks. The talent requirements to produce a good show are the same, but there aren’t suddenly twice as many talented people available to do the work. The chart above might now look a little something like this:

| Show quality | Talented staff per show |

# of shows | Total talented staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently great | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Excellent | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Very good | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Good | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| Sometimes good | 2 | 21 | 42 |

| Generally poor | 1 | 75 | 75 |

| Unwatchable – bad | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| Total | 120 | 150 | |

Notice how many shows had to drop into the lower categories to make this work. The contrast is really obvious when you look at the two outcomes side-by-side.

With twice as many total shows, there are fewer shows that are even sometimes good. By doubling the total output, there are fewer than half as many shows that are ever acceptable to the audience. And there are only a third as many shows that are usually good.

These numbers are obviously a gross oversimplification, but they illustrate a point: By increasing the output without increasing a limited, but required resource the overall quality declines faster than the total output increases.

500 channels and nothing’s on

Now fast-forward to today. There are literally hundreds of networks trying to fill 24 hours every day. Sure, with the amount of money available in the industry today there may be more people willing to work there.

But if my assumption is at all close to reality, then we would expect to see shows that clearly don’t have anyone talented working on them. We might even see shows where they simply send a camera crew out to film people without a script. We might call this a “reality” show.

So you’re not in the TV business. How does this apply to you? Everywhere in the example above, replace “talented staff” with “attention”. How much undivided attention do you have each day? How many ways are you dividing it? By trying to do more things, are you doing fewer things well?